How to find your purpose in life: 12 powerful exercises to help you discover purpose and passion

Happy blogiversary! Twelve years ago today, I launched a humble little blog about personal finance — this blog, Get Rich Slowly. It was meant as a way for me to share the things I was learning as I dug out of debt. It turned into so much more.

For the next couple of weeks, I’m on the road in the southeastern U.S., speaking to people about personal finance and meeting with readers.

This morning, for instance, I spoke to the 76 people attending Camp FI in Spring Grove, Virginia. My topic? No surprise: The importance of having purpose in your life. As you can see, I am a PowerPoint genius…

If you’ve spent any time reading my material, you know that I believe purpose is the foundation on which all plans — financial and otherwise — ought to be built. Purpose is a compass. It helps you set big goals, sure, but it also acts as a guide when times get tough. Your mother died? Your wife left? Your husband lost his job? If you know what your primary purpose is in life, these stressful events are much easier to deal with.

For this presentation, I added a new twist. You see, a lot of folks who are interested in money tend to pick things like “getting out of debt” and “becoming financially independent” as their purpose or mission. But I think these are poor choices.

I’ve seen far too many folks make debt elimination a goal — then fall right back into debt once they’ve achieved it. And there are plenty of people who reach FI (or retire early) only to find they no longer know what to do. (It’s like aiming to reach a certain weight instead of choosing to make lasting lifestyle changes that lead to weight reduction.)

Instead, I think it’s important to recognize that your financial situation should be side effect of pursuing some greater purpose. Financial independence ought not be your aim; it’s merely a means to an end.

When I speak about purpose (which is often), I tend to fall back to the George Kinder/Alan Lakein personal mission statement exercise. I feel like it’s one of the best available tools for helping people find focus. But it’s not the only tool.

Today, to celebrate this site’s twelfth birthday, I want to present twelve alternative exercises for discovering your purpose and passion. If you’ve tried one (or more) of these without success, try another. One of them is sure to be useful for you.

Note: I’ve done my best to credit sources for these exercises. (Many come from Barbara Sher’s excellent book Wishcraft, which is all about crafting the life you really want.) At the end of this article, I’ll give you a list of recommended reading — and tell you what I think is the single best book for discovering passion and purpose.

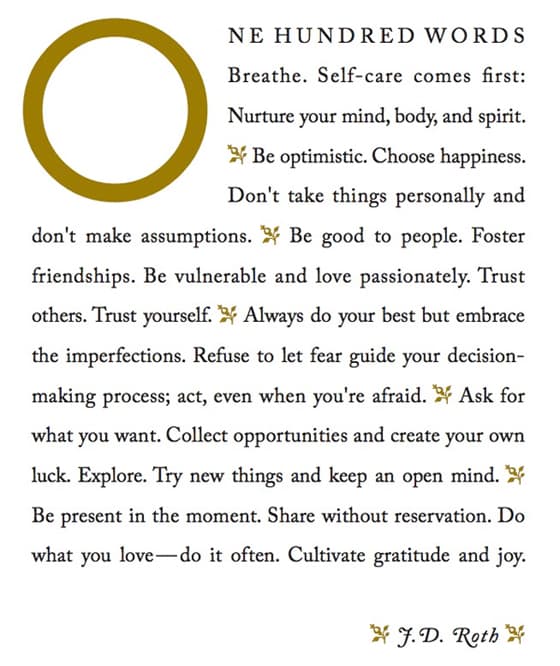

Your One-Hundred Word Philosophy

The first exercise is one I created myself. It’s based on CrossFit’s “world-class fitness in 100 words” statement. There’s no time limit for this exercise, but it could take a while so be prepared.

Your aim is to write out your life philosophy in exactly one hundred words — no more and no less. This can take any form you want, from a statement of values to a list of instructions. Begin by writing down your core beliefs and values. It might also be helpful to think about books that have had a big impact on your life or powerful advice you’ve received in the past. Based on your experience and beliefs, what is your life philosophy?

As an example, here’s my own hundred-word philosophy, which I’ve written as instructions to myself:

Some of those admonitions are my own invention. Some come from books like The Four Agreements and The Power of Now. “Refuse to let fear guide your decision-making process,” was advice from my girlfriend. “Create your own luck” is based on my friend Michelle’s advice to “create your own certainty”.

Again: Target one hundred words exactly. It’ll force you to spend time thinking and editing and being introspective.

As you can see, I paid an artist friend to create a pretty letterpress poster of my 100-word philosophy, which I’ve hung on the wall here at home. I look at it every day. Obviously, you don’t have to go that far.

Your Original Self

This next exercise, which comes from Barbara Sher’s Wishcraft, sounds hokey at first. Turns out, however, that it’s a lot of fun to complete. Here’s how it works.

Set aside about half an hour for quiet contemplation. (There’s no writing involved in this exercise — only thinking.) Let your mind wander back to your childhood. Remember what you used to do to have fun — especially those times you especially treasured. When you were allowed to daydream or do whatever you wanted, what did you choose to do?

Try to answer these questions:

- What sorts of things attracted and fascinated you when you were a kid?

- What sense — smell, sight, hearing, taste, touch — did you live through most? Or did you enjoy them all equally? What kinds of sensory experiences do you remember best?

- What did you love to do (or daydream about), no matter how silly or unimportant it might seem now? Did you have secret aspirations and fantasies that you never told anyone about?

After thirty minutes of unstructured reverie, ask yourself a couple of questions. First, do you feel like there’s a part of you that still loves the things you loved as a child? What do you miss most? Next, ask yourself what talents or abilities these childhood dreams and passions might point to in the present. What can you do today to reconnect with some of who you were as a kid?

As I mentioned, I enjoyed this exercise. Although you don’t have to, I wrote down what I liked as a kid:

When I was a kid, I loved the outdoors. I loved to run and play outside. We lived in a small trailer house but were surrounded by acres and acres of land. We had freedom to romp across the fields, explore the nearby woods and orchards, and to browse the banks of the creeks. My favorite family vacations were those that involved camping. (Unfortunately, there weren’t many.)

I loved looking at the insects and the plants. I liked digging in the dirt. I liked finding bones and rocks and shards of glass. I enjoyed playing games outside — tag, dirt clod fights, whatever. I especially liked building forts. I liked going down to the “big tree” and hanging out under its branches.

Yes, there’s still a part of me that loves this sort of thing. I think that’s one of the reasons I’ve come to treasure the morning walks with the dog. It’s an opportunity for me to explore the same stretch of ground over and over and over again. I truly enjoy watching how the woods and fields change a little every day. And that’s probably one of the big reasons I enjoyed the RV trip. It forced me to connect to the world outside in a big way.

What talents and abilities might this interest point to? I’m not sure really.

Who Do You Think You Are?

This activity is short but effective.

On a blank piece of paper, spend 5-10 minutes answering the question: Who do you think you are? How would you describe yourself to a total stranger? Be objective. What are most important characteristics that define your identity? There aren’t any right or wrong answers here, and there’s only one rule: Don’t overthink this. Put down the first and surest answers that come into your head, the ones that make you say, “This is me.”

[This exercise also comes from Wishcraft.]Focus on Five

We’ll explore the next exercise in greater depth next week when I write about goals. You’ll find a version of this in nearly every book on productivity or positive psychology. This version is taken from Angela Duckworth’s Grit (which in turn borrowed it from billionaire Warren Buffett, who may have taken it from Alan Lakein).

Here’s how it works:

- Write down a list of your top twenty-five goals (or more). This might seem impossible at first, but give it a try. List all of the projects you’re currently working on, both at home and at work. List all of the things you want to do but feel like there’s no time. List at least twenty-five. More is beter.

- Next, review your list. Which goals are most appealing? Do some soul-searching — it doesn’t matter how — and narrow the list to the five highest-priority objectives. Just five. Circle them (or copy them to another piece of paper).

- Lastly, look at the goals you didn’t circle. “These you avoid at all costs,” writes Duckworth. “They’re what distract you; they eat away time and energy, taking your eyes from the goals that matter more.” Harsh but true.

If you need help prioritizing your goals — it can be tough to sort through so many! — rate each one on a scale of 1 to 10 based both on how interesting it is and how important it is. Then multiply those numbers together. For instance, if one of your goals has an interest rating of 9 (very interesting) and an importance rating of 3 (not that important), its score would be 27. Compare the scores. Higher is better.

Duckworth says that she would add a fourth step to Buffett’s exercise. Ask yourself: “To what extent do these goals serve a common purpose?” The more closely aligned your top five goals are, the better you’ll be able to focus on your passion (or purpose).

When I write about goals next week, I’ll ask you to do a different version of this exercise drawn from Sonja Lyubomirsky’s The How of Happiness.

A Letter to the Future

Here’s another exercise that’s common in self-help manuals. You’re going to contemplate and describe the personal legacy you’d like to leave in this world.

Think about how you want to be remembered by your grandchildren or great-grandchildren. (If you’re childless like me, you’ll have to pretend.) In the form of a first-person letter, write a summary of your life, values, and accomplishments as you’d like them known to your descendants. Pretend like you’re near the end of your life and want to share the “greatest hits” version of your personal story for posterity.

One common way to approach this is to pretend you’re writing your own obituary. In The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen R. Covey offers the following variation:

In your mind’s eye, see yourself going to the funeral of a loved one. Picture yourself driving to the funeral parlor or chapel, parking the car, and getting out. As you walk inside the building, you notice the flowers, the soft organ music. You see the faces of friends and family you pass along the way. You feel the shared sorrow of losing, the joy of having known, that radiates from the hearts of the people there.

As you walk down to the front of the room and look inside the casket, you suddenly come face to face with yourself. This is your funeral, three years from today. All these people have come to honor you, to express feelings of love and appreciation for your life.

As you take a seat and wait for the services to begin, you look at the program in your hand. There are to be four speakers. The first is from your family, immediate and also extended — children, brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces, aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents who have come from all over the country to attend. The second speaker is one of your friends, someone who can give a sense of what you were as a person. The third speaker is from your work or profession. And the fourth is from your church or some community organization where you’ve been involved in service.

Now think deeply. What would you like each of these speakers to say about you and your life? What kind of husband, wife, father, or mother would you like their words to reflect? What kind of son or daughter or cousin? What kind of friend? What kind of working associate?

What character would you like them to have seen in you? What contributions, what achievements would you want them to remember? Look carefully at the people around you. What difference would you like to have made in their lives?

Make no mistake: This can be a powerful exercise. Tear-inducing, even. That’s okay. By thinking about how you’d like people to remember you in the future, after you’re gone, you can take steps to align your present self and actions with that ideal vision.

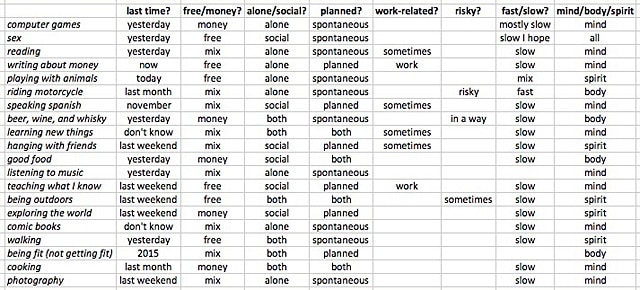

20 Things You Like to Do

Here’s another exercise from Barbara Sher’s Wishcraft. She says she borrowed it from Sid Simon’s Values Clarification.

To begin, list twenty things you like to do. You must come up with twenty. That’s the only rule. Don’t cop out and make a list of four things you like to do. Or twelve. List at least twenty. (You can write down more, if you like.)

Now you’re going to make a chart.

Take a fresh piece of paper. Down the left side of the page, in the first column of the chart, copy your list of twenty things you like to do. (The order is completely unimportant.)

Now, across the top of the page create 8-10 columns. Label them like this (you might have to write tiny): How long since you last did this activity? Free or costs money? Alone or with somebody? Planned or spontaneous? Job related? Physical risk? Fast-paced or slow-paced? Mind, body, or spiritual?

Feel free to add other categories that occur to you. (At home or in the world? Spouse likes also? Enjoyed a decade ago? Whatever. It’s your list.) Now go through your chart and fill it out for each of your interests.

What patterns emerge? What do these patterns tell you about your self and life?

To illustrate what this chart ought to look like, I did the exercise myself. It was enlightening. And it took me longer to complete than I expected. I could come up with sixteen things I like to do, but expanding the list to twenty was tough. Here’s a screenshot of my list. (Because I’m a nerd, I used a spreadsheet instead of a piece of paper.)

Kind of sad (and hilarious) to note that this list is in the order I thought of things. So, that means “computer games” came to mind as something that I like to do before “sex” did. Yikes!

Looking at my list, it seems like I do a pretty good job of doing the things I like to do. Not perfect but good. There’s also a good balance of free activities vs. activities that cost money, and an even divide between social and alone time. But it’s clear that most of the things I like to do are spontaneous, not work-related, mental, and — most of all — slow. The only activity on my list that’s truly adrenaline-inducing is riding my motorcycle.

Who Do You Want to Be?

This exercise is based on a conversation I had with my friend Tyler Tervooren.

On a blank piece of paper, make a list of qualities and habits you’d like to develop. Do you want to ride your bicycle every morning? Do you want to be more patient with your children? Do you want to be more helpful to your co-workers? Do you want to read the Bible every day? Do you want to drink less alcohol?

It doesn’t matter what order you write these in. Take as long as you need to make your list.

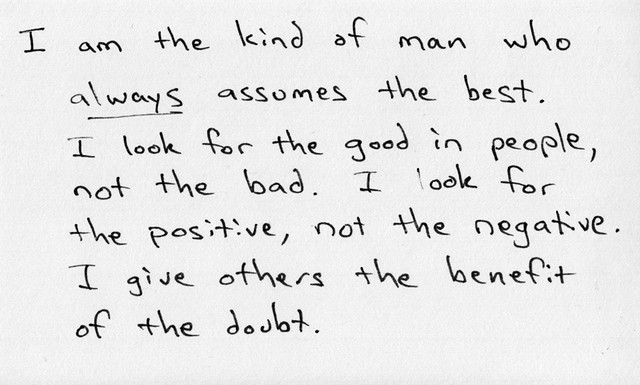

When you’ve finished, reframe each item using the following format: “I am the kind of man who [blank]” where [blank] is the habit or quality you’re trying to develop. (And obviously, if you’re a woman please reframe each of these as “I am the sort of woman who [blank].”)

For example, if you wrote down that you’d like to get in the habit of waking 10,000 steps every day, you might reframe that as: “I am the kind of woman who walks 10,000 steps every day.” Or, better: “I am the kind of woman who walks everywhere she can.”

If one of your aims is to talk less about yourself and pay more attention to others, you might write: “I am the kind of man who listens first and talks second. I’m genuinely interested in what others have to say.”

Now copy each of these sentences onto an index card — one for each habit. Place these index cards by your bedside. Every morning when you wake up, train yourself to look at these cards first thing. Read through all of them to remind yourself of the habits and qualities you’d like to develop. Finally, choose one to make your focus for that day. Keep it in mind as you go about your normal routine, and do your best to live up to the affirmation.

Tyler says this habit helped him make real and lasting changes to his life. He built new habits to replace some of the tendencies that had been giving him trouble.

Who You Might Have Been

Imagine you grew up with all of the resources — financial, emotional, educational — you could have possibly wanted or needed. Your interests were encouraged and fostered. You had help and encouragement in all that you did. You weren’t limited by time or money or location. In a perfect world, what do you think you would be doing now? What would you already have done? What kind of person would you be?

Think big. Be as extravagant and far-fetched as you’d like. What’s the one big dream you would have pursued if everything had gone your way? If you really would have wanted to become President, then say you’d be President. If you would have become a movie star, say you’d be a movie star. Don’t hold back. Let your imagination fly free in whatever direction it desires.

Don’t pull any punches. Answer truthfully. Describe what this ideal life might look like.

[This exercise also comes from Wishcraft.]The Ideal Schedule

In David James Duncan’s The River Why, Gus, the main character, decides at a young age that in an ideal world he would fish 14-1/2 hours per day. He’s still in high school when he formulates the following plan:

The Ideal 24-Hour Schedule

- sleep: 6 hours

- food consumption: 30 min. (between casts or while plunking, if possible)

- school: 0 hours!

- bath, stool, etc.: 15 min. (unavoidable)

- housework and miscellaneous chores: 30 min. (yards unnecessary; dust not unhealthy; utilitarian neatness easily accomplished)

- nonangling conversation: 0 hrs.

- transportation: 45 min. (live on good fishing river)

- gear maintenance/fly-tying/rod-building/log-keeping, etc.: 1 hr. 30 min.

- fishing time: 14-1/2 hrs. per day!

Then, in true money boss fashion, Gus brainstorms ways he can pursue his purpose:

Ways to Actualize Ideal Schedule

- finish school; no college!

- move alone to year-round stream (preferably coastal)

- avoid friendships, anglers not excepted (wastes time with gabbing)

- experiment with caffeine, nicotine, to eliminate excess sleep

- do all driving, shopping, gear preparation, research, etc. after dark, saving daylight for fishing only

Result (allowing for unforeseeable interruptions): 4,000 actual fishing hrs. per year!!!

I love it. (And I intend to use this example in future talks, so be prepared.) Gus knows his purpose and by brainstorming his ideal schedule, he’s able to figure out ways to put this dream into action.

In Wishcraft, Barbara Sher suggests a similar exercise. Here’s how it works.

Grab paper and pen. Seclude yourself somewhere quiet. Close your eyes. Imagine your ideal day. Imagine a day that would be perfect if it represented your usual days — not a vacation day. Just a regular, average day if your schedule were ideal. Spend a few minutes visualizing what such a day would look and feel like.

Once your ideal schedule begins to become clear, write down what it’s like in the present tense and in detail — from getting up in the morning to going to sleep at night.

I might say, for instance: “I wake up at 5:30 already in my gym clothes. I grab a piece of fruit, hop on my bike, and ride to the gym. I do an hour of Crossfit. I ride home, grab the dog, and take her for a walk. When we get back to the house at around 8:30, I spend four hours writing about money.” And so on.

As you write about your ideal day, think about the following: What’s the first thing you do when you wake up? What do you have for breakfast? Do you make it yourself or does somebody bring it to you? Do you take a long, hot bath? Or do you take a cold, bracing shower? What clothes do you wear? How do you spend your morning? How do you spend your afternoon? How do you spend your evenning? At each time of the day, are you indoors or outdoors? Quiet or active? With people or alone?

As you envision your ideal schedule, focus on what, where, and who.

- What are you doing? What kind of work? What kind of play? Don’t limit yourself. If you’d like to sing or sail but don’t know how, in this fantasy you do know how.

- Where are you? What kind of place, space, and situation? Are you on a farm in rural England? In a New York office building? On a sailboat in the South Pacific? In a fully-equipped workshop? Again, you’re not on vacation. You’re imagining a normal day — but an ideal day. Where are you?

- Who are you with? Who do you work with? Who do you live with? Who do you talk with? Who do you sleep with? Maybe it’s the same people you work and sleep with already. Maybe it’s somebody else.

Let your imagination go. Don’t put down only what you think is possible — put down the kind of day you’d like to live if you had absolute freedom, unlimited means, and all the powers and skills you’ve ever wished for.

Note: Before (or after) you complete the “ideal day” exercise, you might find it useful to figure out how you actually spend your time right now. For that, I suggest performing a week-long time inventory. On the advice of Paula Pant, I tracked my time last summer and it was very enlightening. It helped me see where I was frittering away my minutes and hours. For more info and instructions on doing a time inventory, visit Laura Vanderkam’s website where you can grab free downloadable PDF forms and spreadsheets to help track your time in fifteen-minute increments.

What Color Are You?

This exercise from Wishcraft is for the more right-brained artistic folks. You analytic engineer types might not like it. (On the other hand, it might be good for you to actually complete it!) Here’s how it works.

Choose a color that represents you. It might be your favorite color or it might not. It ought to be a color that, at this moment, feels like you. The best way to do this is to have an array of colors in front of you. If you have a box of crayons, go get it. If not, here’s a page with a bunch of colors.

You’re now going to role-play that color. You are going to pretend you are that color. You’re going to think like that color, speak like that color, act like that color.

Take a sheet of paper. Write: “I am red” or “I am orange” or “I am carnation blue”. Do not say “I like blue because…” or “I think blue is…”. For the rest of this exercise, you are that color.

Now, in a few sentences to a few paragraphs, describe what qualities you have as that color — not as yourself. For instance: “I am dark blue. I’m quiet and deep like the ocean.” Or: “I am yellow. I’m bright and cheerful, intelligent and warm.

There are no right answers to this exercise. If you’re black, be black! I think Suzanne Vega’s “Small Blue Thing” is a great example of what you might do with this activity.

What color am I? I’m orange, of course.

The 14-Word Description

This exercise comes from my friend Amy Jo. Several years ago, she did a photo project in which she took portraits of people she knew. Before each session, she asked the subject: What are the fourteen words that best describe you?

For our purposes, I want you to brainstorm as many words as possible to describe who you are. You should come up with a minimum of fourteen, but it’s better to brainstorm more. Don’t ask others to describe you. Your aim here is to describe yourself. How do you see yourself?

If you come up with more than fourteen words to describe yourself, narrow the list to only the fourteen that fit you best.

Lastly, for each word write a short sentence that describes why you chose it. For instance, if one of your words was athletic, your descriptive sentence might be, “I enjoy playing sports and being outdoors.”

Here are the fourteen words I chose to describe myself six years ago. (They’re all still accurate.)

- Adventurous – I love to try new things.

- Creative – I love to make new things.

- Curious – I love to learn new things.

- Evolving – I’m a different man today than I was yesterday.

- Independent – I make and act on my own decisions.

- Intelligent – I am smart.

- Playful – I like to joke and jest.

- Positive – I look on the bright side.

- Resourceful – I search for ways to get things done.

- Sociable – I enjoy the company of others.

- Tenacious – I pursue my goals with vigor.

- Unguarded – I share myself freely, and I accept the word of others.

- Versatile – I am good at many things.

- Zealous – I’m passionate about my friends and hobbies.

Here’s one of the portraits from our 14-words photo shoot. I look so serious!

![J.D. looking sinister [Amy Jo] J.D. looking sinister [Amy Jo]](https://www.getrichslowly.org/wp-content/uploads/27203637578_485d697e5c_h.jpg)

When I gave Amy Jo my list, she made an interesting observation. “When adults do this exercise, their words are always positive,” she told me. “But when kids do it, they describe themselves using both positive and negative words. It’s as if they’re more aware of their shortcomings — or at least more willing to admit them.”

Three Questions about Life Planning

Last of all, here’s the exercise I use most often. The father of the life-planning movement, George Kinder, is a certified financial planner and the author of The Seven Stages of Money Maturity. To identify and clarify your direction in life, Kinder suggests thinking about three hypothetical situations:

- Imagine that you have enough money to take care of your needs, now and in the future. How would you live your life? Would you change anything? What would you do with the money?

- Now imagine that you visit the doctor and she tells you that you have 5-10 years left to live. She says that you won’t feel sick, but you’ll have no notice of the moment of your death. What would you do in the time you have left? Would you change your life? How?

- Finally, imagine your doctor shocks you with the news that you only have 24 hours left to live. If you only had a day remaining, what dreams would you leave unfulfilled? What would you wish you had finished? What would you wish you had done or been? What would you have missed?

These questions — which are based on the work of time-management guru Alan Lakein — are powerful tools for figuring out what you want out of life. If you take the time to really ponder them and answer them honestly, they can help you clarify your personal values and set meaningful goals.

Over the past five years, I’ve shared this exercise with hundreds of people. Many who took it seriously have written to tell me it changed their lives. It changed my life too. Maybe it’ll change yours.

Recommended Reading

In this article, I’ve done my best to credit sources. A couple of these exercises are my own — the hundred-word exercise, for instance — but most are not. Most are borrowed from books. But there are plenty of excellent books out there that can help you figure out what you want out of life even if they don’t ask readers to fill out forms our meditate on what’s important.

Victor Frankl’s classic Man’s Search for Meaning, for example, is a work that almost everyone refers to. It’s a ground-breaking short book about how to find purpose even under the worst circumstances. But it doesn’t contain any reader homework.

Here then are a few of my favorite purpose-related books. You might like them too:

- Man’s Search for Meaning by Victor Frankl

- The Seven Habits of Highly-Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

- Wishcraft by Barbara Sher

- The How of Happiness by Sonja Lyubormirsky

- How to Get Control of Your Time and Your Life by Alan Lakein

- Essentialism by Greg McKeown

To my mind, however, the best book on this subject is relatively new: Angela Duckworth’s Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. This was my favorite book of 2016. If I could make it required reading, I would. It’s that good. I’ve listend to the audio version nearly a dozen times (including yesterday during my 21-hour trip home from Florida).

Grit is dense with information and ideas. Duckworth makes a convincing argument that passion and perseverance — or, in Money Boss lingo, purpose and patience — are the best predictors of success. If you can hone in on a single top-level purpose then doggedly pursue it, your life will be filled with meaning and happiness. Great stuff. I hope to publish a review of the book sometime soon.

As I said at the start, your purpose is your compass. Its your mission. It’s what gives your life direction and meaning. To support your purpose, however, you’ve got to set up a personal action plan built around a hierarchy of goals.

Next week, I’ll share some thoughts (and exercises) on how to set goals and structure life to pursue your purpose. How do you put your personal misson statement to use? We’ll talk about that in just a few days.

In the meantime: Tell me about your purpose. What is it? Do you have a personal mission statement? Which of these exercises do you find effective? Are there others that are better?

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)